“Without Monzer, there would be no technology,” says Zhifeng Ren, director of the Texas Center for Superconductivity, co-lead researcher and one of Hourani’s filter co-inventors, with UH postdoctoral fellow Luo Yu. The three are listed on the patent application, filed last fall.

Ren, who currently also serves as IVP’s scientific advisor, considers the filter among his most important projects.

“It is a revolutionary invention” that allows owners of schools, restaurants, airports, stores, hotels, theaters and all other buildings “to take action today,” says Kenneth Thorpe, executive director of Emory University’s Institute for Advanced Policy Solutions. “The filter has economic importance and will have an impact on morbidity and mortality,” predicts Thorpe, who came upon IVP last summer while researching air purifiers. Impressed with the filter as different from others, he joined IVP as a consultant, to make the filter’s economic and public health case.

Portable Unit for Easy Toting

Hourani’s earlier inventions are trumped by the filter. IVP deployed mobile devices first because heating, ventilating and air-conditioning (HVAC) system retrofits—with perhaps the biggest potential for impact—are not as simple to deploy as a plug-in unit.

The HVAC application, fitted to existing or new commercial or residential buildings, will debut within two months, according to the Hunton Group, which distributes HVAC systems and products and is partnering with IVP. Hunton’s team is working out the logistics for a “cost-effective retrofit,” says R.O. Hunton, chairman, who declines to offer details so Hunton can stay ahead of the competition (see p. 8).

“We are very, very bullish on the filter,” says Hunton, who was not any easy sell. “Protective of our reputation, we did a lot of research before we agreed to represent this product,” he says. “It’s the only one we were able to find that captured the virus and then instantaneously killed it. And it didn’t increase the air-conditioning load because of the way it was designed and the use of nickel foam.”

This year, IVP launched a lightweight portable unit designed to fit into a backpack for easy toting. It cleans a 240-sq-ft area. A larger-venue mobile unit for airports and retail malls, described as an air vacuum that roams the space on a customized electric cart, begins beta testing May 1. A face shield and an automobile filter are in the final stages of R&D. Hourani even has plans for a mini-filter that fits into an elevator cab. And he is working on a version that can be retrofitted into a car’s HVAC system.

Hourani decided to deploy to schools first. The Slidell Independent School District (ISD), which draws 345 pre-kindergarten through grade-12 students from four rural counties in northeast Texas, debuted the system last August. Slidell has nine units to help protect students and 52 employees in its two buildings.

Remote learning last spring, prompted by the pandemic, was a big problem because half the student body did not have the technology needed or good internet or cell phone signals, says Taylor Williams, the school superintendent. Students fell three months behind in their studies, she says.

“In June, the principals and I knew there was no way we were going to be able to make remote learning work after the summer break,” says Williams. But in-person learning was going to be more difficult, especially since it had become clear that transmission was primarily through droplets, she adds.

Then, in July, the region’s state representative, Phil King, called Williams to inquire whether Slidell wanted to be the first school demonstration site for the filter. Not believing her ears, Williams did some research and accepted the offer.

The IVP units, mostly paid for with $12,500 of CARES Act funds, arrived and were plugged in on Aug. 18, the day before school started. Within six weeks, attendance was better than ever, at 98%.

“The COVID numbers around us, in other districts, kept going up, but we never spiked,” Williams says. A side benefit was that there was no strep and no flu this winter. “This filter is here for the long term to keep our kids well, and it gives the staff and our parents a sense of safety and security,” she adds.

Williams has had inquiries from other superintendents. One came last summer from Kelli Moulton, the recently retired superintendent of the Galveston ISD, which serves 7,000 students on 13 campuses.

Galveston has since made a $100,000 investment in 78 classroom-size machines and 45 larger units for gyms, libraries and cafeterias. Again, CARES Act funds helped.

In Galveston, 88% of students are back in school. “I don’t think there is any metric solid enough now to determine the effectiveness” of the units in preventing the spread of COVID-19, especially because people can be exposed elsewhere, says Moulton. “But it’s one way to make people feel more comfortable,” she adds.

Moulton is such a fan of the filter that in February she signed on as a Hunton consultant. As the educational and governmental leader for IVP distribution, she is working through a list of superintendents in the more than 1,200 school districts in Texas. She started with the areas that have the most COVID-19 cases.

IVP units are currently in buildings in 45 states and Dubai, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, South Korea and Hong Kong, says IVP. The filters are in more than 100 public and private hospitals, including COVID-19 facilities. Two convention centers are outfitted, with a third on its way. Three international hotel chains are installing them.

Number of Installations Growing

The number of installations keeps growing, mostly but not exclusively in Texas: schools, early childhood centers, nursing homes, municipal buildings and gyms. The 250,000-sq-ft Canyon Ranch Spa in Las Vegas now has units. And the number of office buildings with units also is growing.

IVP is in partnership with Asset Living, a student housing provider, and Greystone Senior Living. And it is working with Medical Properties Trust, which provides capital for hospitals, and the Steward Health Care Network.

IVP deployed units to Michigan’s Wayne County Jail. And the U.S. Dept. of Defense has granted IVP $750,000, coming in three installments, to develop the technology for war zones.

Hourani’s other bright ideas, inspired by problems, include an application for post-tensioned slabs on grade to prevent cracking (far left); an oil skimmer to clean up spills; and a patented temporary window brace to keep glass from shattering under strong hurricane winds. PHOTOS AND IMAGES COURTESY OF MONZER HOURANI

In coming weeks, IVP will be presenting to state COVID-19 task forces in California, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Florida, Arizona and Nevada, says Peel.

Hourani is proud of his 10-person IVP team. And he is equally impressed by his 25-person Medistar team.

“In these times, to be able to forge ahead, finance and deliver the largest public-private partnership outside College Station for Texas A&M University is nothing short of a miracle,” he says, referring to a $550-million student housing, biomedical and life-sciences project under construction at the Texas Medical Center.

In downtown Phoenix, Medistar hopes to break ground this year on a $300-million apartment, office, retail and student housing project that encloses 1 million sq ft, located at Central Station. “Monzer’s keen attention to detail is what sets him apart from other developers,” says Christine Mackay, the city’s economic development director. “He challenges everyone to be their best.”

Hourani has close relationships with collaborators. “His performance as a developer is without peer,” says William Harlan, chairman and CEO of Ascend Medical Holdings, which invests in health care properties.

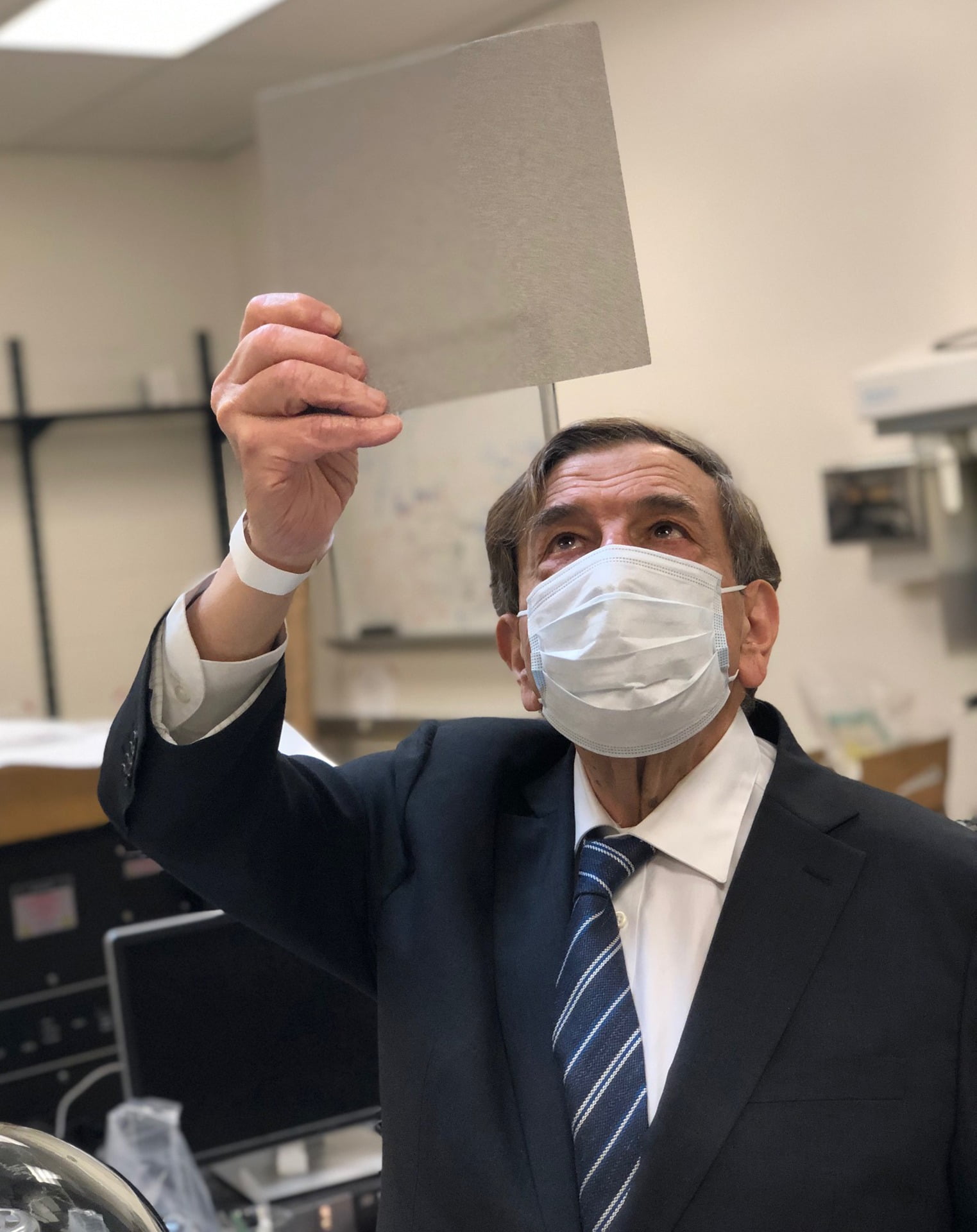

Despite his accomplishments, Hourani—who was vaccinated several months ago and wears a mask in public places that don’t have IVP filters—is under stress on several fronts.

He has long felt responsible for the care of relatives in Lebanon, which remains in deep turmoil. And the pandemic and its economic ramifications for Medistar—financing is tight, projects are on hold—are weighing heavily on his shoulders. “I am spread between all of this,” he says.